|

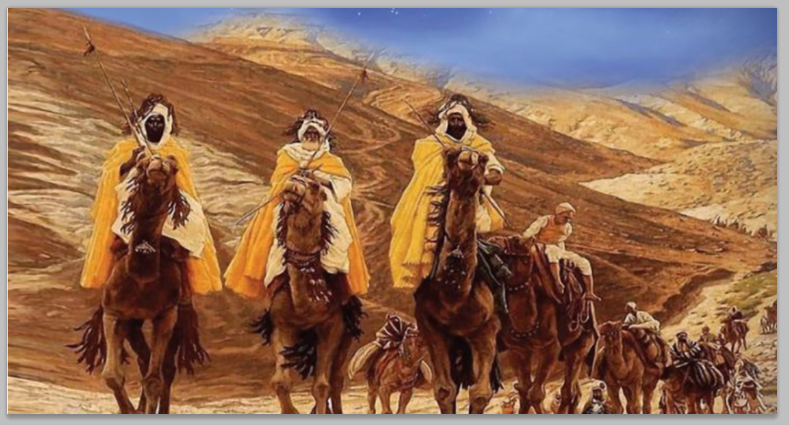

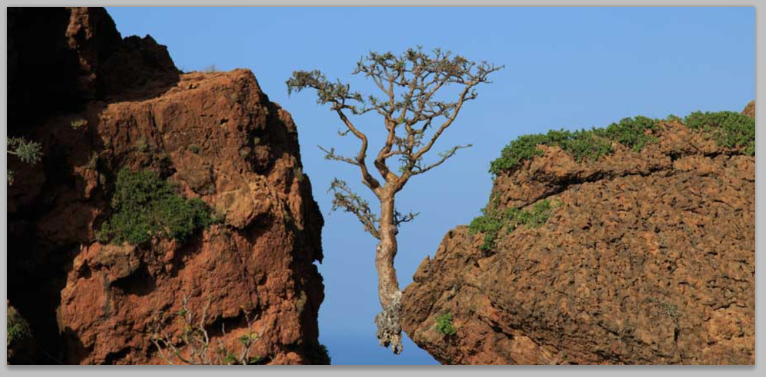

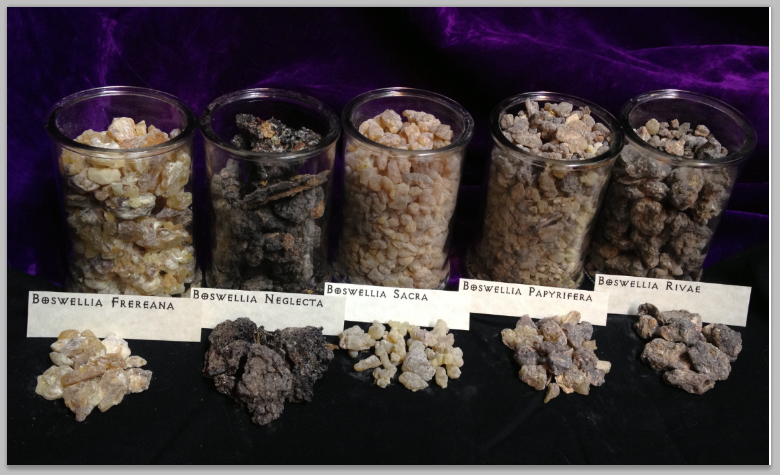

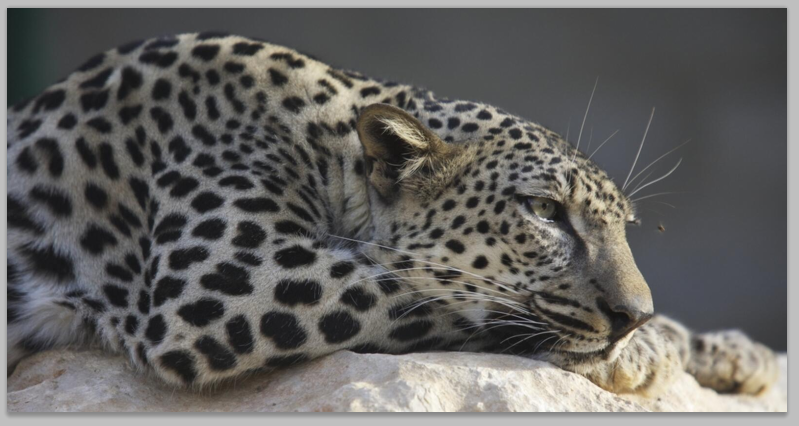

I would guess that if you've ever heard of Frankincense and Myrrh, it probably has something to do with the Magi. According to the biblical account, the Magi (they are variously described as wise men or magicians or kings though probably astronomers too) followed a bright and portentous star from the East (possibly Persia, maybe even China) toward the small town of Bethlehem where they came upon an infant child with his mother and they presented the gifts of Gold, Frankincense and Myrrh. We know what gold is but what exactly are Frankincense and Myrrh? I describe them as the Tears of Trees Both Frankincense and Myrrh have long been revered from Ancient Greece and Egypt, used in the Jewish, Christian and Muslim faiths and were traded eastward in antiquity with India and China both as incense and for medicinal purposes. Frankincense and Myrrh were valuable commodities that were exported by camel caravans throughout the then, known world. As only royalty or the wealthy could afford either, they made for easily transportable but worthy gifts when travelling. Both were used in embalming and purification of the dead, whilst in other religious rites they were burned as incense. Both were also used for fragranced oils and for their medicinal properties. The botanical name for Frankincense is Boswellia, a tree that thrives in the arid, cool areas of the Arabian Peninsula, East Africa and India and is considered unusual for its ability to grow in environments so unforgiving that they are sometimes known to grow out of rocks. The finest and most aromatic of this species is Boswellia sacra found in areas of Somalia, Oman and Yemen. These trees, which grow to a height of 5m, have papery bark, sparse bunches of paired leaves, and flowers with white petals and a yellow or red center. Frankincense, which has been used for perfume and incense for some 6,000 years, is critically endangered, half the world’s supply lies in Somalia and Eritrea, often surrounded by a war with no end in sight (a peace agreement was signed in Eritrea in 2018 after 20 years of bloodshed). Myrrh is harvested from species of the Commiphora tree which is native to northeast Africa and the adjacent areas of the Arabian Peninsula. Commiphora myrrha, the tree most commonly used in the production of myrrh (the biblical myrrh is Commiphora guidottii), is found in the shallow, rocky soils of Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia in Africa and in Oman and Saudi Arabia on the Peninsula. It boasts spiny branches with sparse leaves that grow in groups of three, and can reach a height of 3m. The processes for extracting the resin of Boswellia (for Frankincense) and Commiphora (for Myrrh) are essentially the same. Harvesters make a longitudinal cut in the tree's trunk, which pierces gum resin reservoirs located within the bark. The sap slowly exudes from the cuts and drips down the tree which, as it comes into contact with air, hardens into 'tears'. These tears are left on the sides of the trees before harvesting takes place, several weeks later. Trees start producing resin when they area about 10 years old and the harvesting is done two or three times a year; the final harvest producing the best quality and the most aromatic of resins and generally speaking the more opaque the resin the higher the quality. Frankincense, once dried, comes in many different forms; its quality is based on colour, purity, aroma, age and shape. Silver and Hojari (Royal Green Hojary) are generally considered the highest grades of Frankincense. Myrrh, however, produces a much darker resin of a reddish brown hue and white streaks have been known to form across the surface as it ages. Although darker, Myrrh commands a higher price across the markets of the world. The scented resins from these species are still largely collected from wild trees and remain precious due to their rarity, starkly illustrated by their near-threatened conservation status. Mature trees of both Boswellia and Commiphora can yield up to 3kg of resin per year and with Frankincense selling for about €65/kg and Myrrh for about €95/kg, it makes them a valuable regional crop, as Frankincense is exported by the thousands of metric tonne each year. But as demand increases, ecosystem degradation, over-exploitation and conversion (clearing) of Frankincense woodlands to provide for agriculture are bringing tree populations to the brink of collapse. A study published in Nature Sustainability this year estimates that without new trees to replace the old, half the intact forests — and therefore half the F.rankincense they produce — will be gone within 20 years. Boswellia papyrifera — the species responsible for most of the world’s Frankincense are ancient trees, the trees are old and dying, and most haven’t produced a young tree in half a century. Despite adult trees producing plenty of seeds, researchers seldom found any new saplings, let alone newly matured trees. The local people burn the forests for agriculture and allow livestock that graze in forests to eat the saplings. The tree tappers, who make only a tiny percentage of the Frankincense profit and rely on it for income, try to take as much resin as they can in the shortest amount of time, exacerbating the problem. The European demand for Frankincense is growing and the extracts (usually oils but in the raw form too) have great potential as health products. The oil is also used in aromatherapy to relieve stress and anxiety and as an aid aimed at healthier joints. However, supplies of wild-collected resins are decreasing, therefore, sustainability is key but the increase in demand for harvesting has led to increased pressures on the wider natural environment and rare Arabian leopards have been forced out of traditional ranges by Frankincense harvesters. The Tears of Trees and Leopards too, it seems

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

WildEdges

A haven of quiet countryside highlighting issues affecting the natural world. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed